“The potential loss of thousands of screens will only hasten the day when Hollywood doesn’t have to deal with those pesky exhibitors anymore.”

—Gary Susman, RollingStone.com, September 4th, 2013

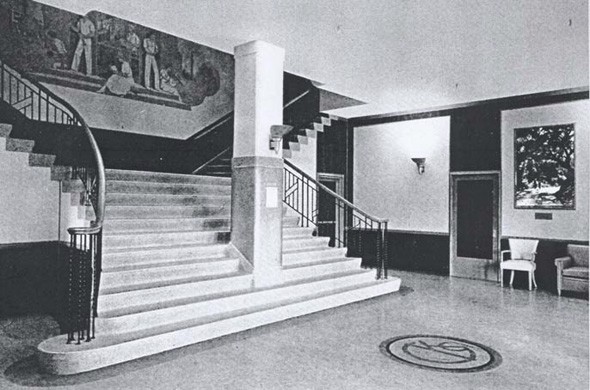

Now on this third post, it’s become very clear to me that the digital conversion is old news. It was the talk of the industry before I became part of the business and even prior to my involvement with the Elks Theatre. And yet, we are likely one of hundreds of small town cinemas in the nation that didn’t get the memo early enough. And now we’re left behind.

Was this part of the plan?

Given the entire nature of the digital conversion combined with the choke-chain relationship studios have held on exhibitors, with no flexibility for even small venues, one can only wonder if independent cinemas are seen by Hollywood as an expendable part of their current business model.

Whether this is true or not, there are a number of factors that have lead to the current downward spiral for small cinemas like ourselves.

Who’s to blame for film print shortage?

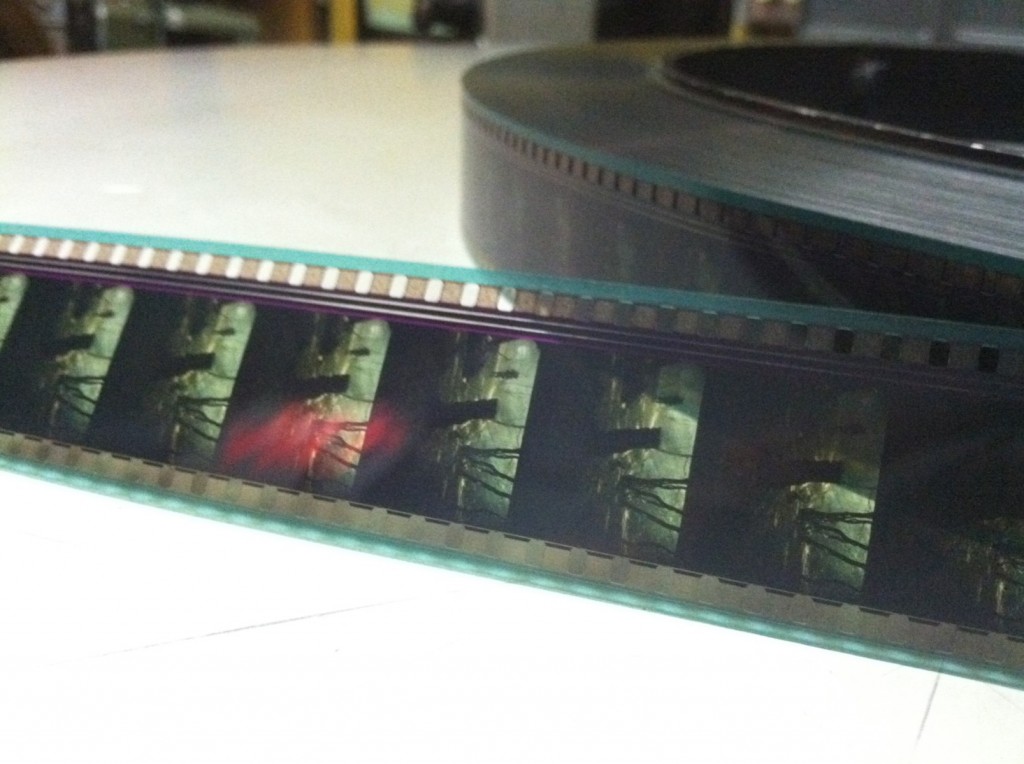

In my last blog, I talked about the limited amount of prints major distributors are issuing. However, studios aren’t entirely to blame for whether prints are available. Ken Tsujihara didn’t suddenly wake up one day and think “We’re only going to order 1,000 prints of Desolation of Smaug to starve out those indie shingles.” As fun as it can be to point fingers at a single entity, it’s not that simple.

Instead, by pushing the DC and having more and more theaters convert, fewer prints are needed in circulation overall. That means shrinking business for film manufacturers, and a result, many have closed their doors within the past five years because of lack of demand.

This is why film prints are so difficult to get.

And when the highest grossing theaters get priority for prints, whether a cinema is first or second run, it becomes a little harder each weekend to get a movie.

$80,0000-$100,000 Buy-In

This was the price range for a digital projection system per screen in 2011. And while a monster number, the cost of a projector has gone down due to more brands entering the market. And yet, in 2014, even $50,000 for a reasonable package is still a lot of money.

“Fundraise! Do a kickstarter!” Everyone in my community clamoured.

High capital fundraising isn’t really possible without having some in the bank already. And the people around you need to have the financial stability to give — remember, our median income in Middletown is $42k. Crowdfunding, which we opted not to do, isn’t possible unless you live in a major metropolitan area where many people know and frequent your theater. And remember, people only shop for their own when preparing for a storm.

“$50k? Hooey. Go get a bank loan,” I’ve been told.

For the Elks, and many others, a bank loan isn’t really an option. Back in 2005, our building, which included the cinema and other occupied retail spaces, was purchased itself by the Greater Middletown Economic Development Corporation (GMEDC, the non-profit of which my father is Vice-Chairman) using a $500,000 state-granted sum for the town to use as a revolving loan (to be paid back in only five years) for special causes in town. Even then, the action was to ensure the building and businesses within it would survive in the first place.

And at the rate technology is changing, how can anyone know if at the end of, say a long repayment period to keep monthly costs low, that a newer projector or an expensive upgrade won’t be needed?

Maybe next time the multiplexes won’t be so lucky.

The most well-known piece of assistance

“Did the industry do anything to help theaters? Are they still offering help?”

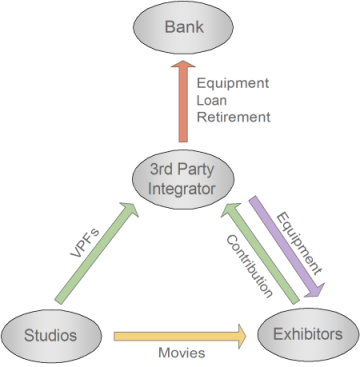

A Digital Cinema Integrator like Sony and Cinedigm provide not just Digital Cinema Packages, but also facilitated the ones means of support for the DC burden: the “Virtual Print Fee” or “VPF.”

When the digital deliverable (the DCP hard drive) is created and sent instead of a film print, studios are realizing significant savings when distributing to theaters. DCP’s are cheaper to make than a film print, and since they weigh much less, shipping costs are very cheap in comparison. A VPF contract was a means for studios to pass on the savings to theaters to help offset the financial burden of the DC.

Of course, you had to invest in (or lease) a digital projector first, so this was a well-intentioned gesture from the industry if you were able to borrow from a bank. See the repayment model below.

But even so, two problems exist:

1. The more screens you have, the more this works in your favor.

Multiplexes are almost always first run theaters because they offer choices for patrons and therefore generate more box office gross, making them more favorable in the eyes of the studios.

First run theaters benefit most from the VPF structure as they receive prints first and then gain from the realized shipping savings. After the initial run, prints (digital or film) make their way to second run theaters in the same region. You can bet your bottom it costs a lot less to ship a drive ten miles than 3,000. It’s clear the second-run take in the VPF program is significantly smaller.

2. Did we mention it was over?

That’s right! Sony ended their Virtual Print Fee program in March 2014, and Cinedigm before them in the fall of 2012. To me, the fact that these companies closed the doors on this so quickly is incredibly frustrating. Especially because we at the Elks Theatre didn’t comprehended our need to convert until the fall of 2012. Meanwhile, Cinedigm continues to expand their VPF offering overseas. I’m sure this only because the international market is much more valuable. “Take care of your own” doesn’t apply here.

“There are no new VPF agreements being made, the ones that were entered will run for 6–7 years, and each day gets us closer to the day there will be none.” —Michael Hurley, IndieWire

***BONUS: And did we mention independent distributors may also have gotten the short end of the stick with virtual print fees?

***SUPER BONUS: Ira Deutchman went on an informative tirade two years ago that sheds even more light on the terrible truths about why VPFs are bad for indie film distribution.

What should have been considered

Does anyone remember the Digital Transition and Public Safety Act of 2005? That was the piece of legislation that dealt with the switchover of television signals from an analog to digital. Sure, it played a major part in our nation’s debt reduction, but it also established a coupon program that would allow Americans to purchase conversion boxes with little to no cost to them whatsoever.

The program behind the subsidized coupons was established by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) and included input from public interest groups and the consumer electronics industries. The NITA could spend up to $1.5mm to assist low-income households with up to two $40 vouchers to pay for their converter boxes, pretty much entirely.

I think you see where I’m going with this… A program similar to the DTPSA could have been developed for the DC. The film industry certainly could have delayed the conversion by a few years and found a better way to help subsidize the conversion for certain American movie theaters. It’s very possible Congress would have listened, especially given the economic repercussions — but then again, sometimes involving the government makes the process longer and more difficult. Yet, a major keystone to a town or community business district like a cinema can make or a break the health of a local economy.

Obviously most larger, chain-owned multiplexes were given the utmost priority to convert, but perhaps a program to enable independently operated cinemas achieve a fast-tracked non-profit status that would allow them to be recipients of a conversion-specific grant would have resulted in a tremendously different situation.

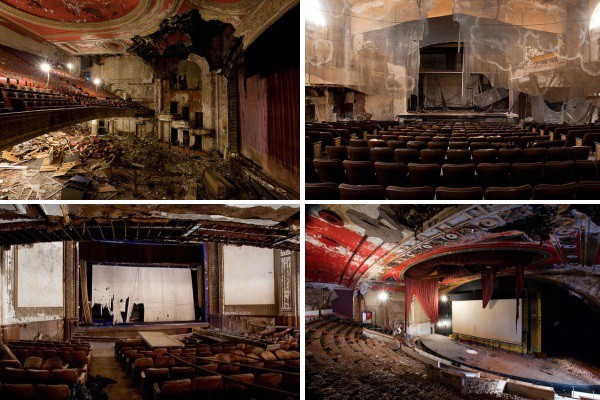

Who’s really at a loss

It’s difficult to tell how many theaters have been lost in the digital conversion. For a major real estate developer, the cost of acquiring a site or building a multiplex from scratch with state of the art digital equipment is more viable than ever. Out with the old, in with the new! But is that always a good thing? And if a cinema closed as a result of being unable to convert and it’s positioned in a low-income area, why would a developer want to place a multiplex there anyway?

I’d bet there are dozens upon dozens of small towns across the country that are now theater-less. Entire populations are now robbed of the communal experience because ticket cost is otherwise too expensive elsewhere or proximity is no longer of convenience.

But alas, as long as the people of China can enjoy our movies…

WAIT.

Are we now outsourcing the communal experience?

Other posts in the series:

BLANK MARQUEE: Struggle of the Homegrown Cinema, Part I

No Accidents in R: Struggle of the Homegrown Cinema, part II

Max Einhorn (@MaxEinhorn) is a producer, writer, and crowdfunding planner. After graduating from Temple University’s film program in 2012, he relocated to New York and worked for Good Machine veterans Anthony Bregman at Likely-Story and Glen Basner at FilmNation Entertainment. Einhorn is currently the Manager of Acquisitions and Distribution at FilmRise, a new distribution company based in Brooklyn. He lives in Manhattan with his girlfriend Cara, also his producing partner. Over the past two years, Einhorn has been a tireless crusader for the survival of his hometown cinema, the 103 year-old Elks Theatre in Middletown, PA.

Max Einhorn (@MaxEinhorn) is a producer, writer, and crowdfunding planner. After graduating from Temple University’s film program in 2012, he relocated to New York and worked for Good Machine veterans Anthony Bregman at Likely-Story and Glen Basner at FilmNation Entertainment. Einhorn is currently the Manager of Acquisitions and Distribution at FilmRise, a new distribution company based in Brooklyn. He lives in Manhattan with his girlfriend Cara, also his producing partner. Over the past two years, Einhorn has been a tireless crusader for the survival of his hometown cinema, the 103 year-old Elks Theatre in Middletown, PA.